by Jens Laigaard

The oldest society devoted to parapsychology is the English Society for Psychical Research which was founded in 1882. Second is the American Society for Psychical Research, organized a few years later. The third society is Danish.

In the evening of November 25th 1905 a handful of people gathered in the back building of 4 Læssøesgade in Copenhagen. They had been invited by Sigurd Trier, graduate in the Faculty of Arts & Science and an ardent spiritualist, and Marx Jantzen, graduate in pharmacology. The meeting was held with the intention of forming a society for “investigating the so-called extrasensory phenomena by unbiased critical experimentation”. All present thought this was a good idea. The Society for Psychical Research was founded and the statutes were solemnly set down.

The committee was made up of nine persons of which at least one, it was courteously resolved, should be a lady. One of the two vice-presidents elected was the renowned psychologist Alfred Lehman. Author of the classic “Overtro og trolddom” (Superstition and magic), keenly interested in occultism and spiritualism, but also a hard-headed sceptic who insisted on tangible evidence.

For president of the society a distinguished and popular person would be preferred. The choice fell on Julius Schiøtt – manager of the Copenhagen Zoo. In the light of the society’s subsequent history there is a cruel symbolism to be found here. But the founders of 1905 were optimistic, and Schiøtt made a fine front man. Later, a member would write that “the memory of this highly gifted, engaging and charming man, who until his death was at the head of the society – although one dare say he was never deeply interested in psychical research – will forever be preserved with deference.”

The membership started at 163 and soon rose to more than 200. The subscription was 1 Danish krone a month. The society was divided into smaller groups who separately set to work on the experimental research. Each group had a medium (who was always a woman) at their disposal, and a supervisor from the world of science, usually a doctor.

These days we speak of ESP and laboratory experiments. Back then, at the beginning of the 20th century, the things going were spiritualism, materializations, automatic writing and table-rapping. Respectable citizens arrived in their best for the evening’s seance in the back building. The lights were turned down, and then the fun began. The tables were rapping so merrily that the occupants of the downstairs flat complained about the loud thumps in the ceiling, and when their complaints were ignored they moved out. Next to go were the scientific supervisors who soon had enough of the cheap tricks played on them by the mediums. The seances continued nevertheless. Many of the common members of the society were deeply committed to spiritualism. They would sit in the half-light, their hands on the tilting tables, and hear spirit voices and see objects float in the air, and feel that they were close to the supernatural world. Although today it may seem naive that people could call this kind of thing “research”, one must nevertheless imagine a certain solemn air to these nightly gatherings.

The period from the start of the society and through the 1920’s was a time of both victories and scandals. One of the greatest triumphs was accounted for by manager Carl Vett as he succeeded in organizing the first international conference for psychical research. This took place in Copenhagen in the autumn of 1921. The Carlsberg Glyptothek made rooms available for the researchers who came from sixteen countries. Papers were submitted by the most prominent names in the field. On the last day of the conference it was decided to establish an international committee for psychical research with Carl Vett as president.

In 1921 the society at long last acquired premises of its own at 7 Gråbrødre Torv. A magazine was published and lectures were delivered. People of note entered the committee, among others the religious historian Vilhelm Grønbech. Good times – on one hand.

On the other hand were the awkward matters, and in the long run these came to predominate.

During the psychic conference some of the foreign researchers participated in a couple of seances with the Danish medium Ejner Nielsen. He had made a specialty of disgorging large quantities of ectoplasm, and this he did so convincingly that the famous researchers took him for the real thing. The Danish society pursued the matter, arranging a series of control seances. In December 1921 the daily B.T. printed a statement by the society to the effect that “Ejner Nielsen is a genuine trance medium, and that portions of white matter may appear in connection with his body in a way which at present is inexplicable, but in any case does not rely on sleight of hand.” Signed Grunewald, engineer, Krabbe, M.D., and Dr. Winther.

Naturally this created a stir. Ejner Nielsen was invited for further tests at Kristiania University in Norway, and the Norwegians sent him back home stating they had caught him cheating. To the newspapers this was heaven-sent. They printed pages and pages on the matter; the readers chuckled and shook their heads. The society was made to look ridiculous and it took years to straighten things out. And then the next scandal was already well under way.

The Ejner Nielsen affair also hurt the society internally. It created a rift between the faithful spiritualists and those of a more sceptical position who thought Nielsen had been swindling – either deliberately or unconsciously. (As for the latter interpretation one must say that a man who is capable of unconsciously cramming a fistful of gauze down his throat is quite a danger to himself.)

The spiritualists outnumbered the sceptics, and their influence was felt very much during the 1930’s and 40’s. While J.B. Rhine at Duke University was busy establishing modern parapsychology using Zener cards, dice, statistics, and ordinary people as subjects for experiments, people were still sitting at 7 Gråbrødre Torv discussing spirits and ectoplasm. When at long intervals it was decided to carry out an experiment, people would start looking not for a subject, but a medium.

In 1921, pending the Ejner Nielsen seances, supervisors Grunewald and Winther privately embarked on a series of experiments to find out whether the human mind could influence swinging pendulums. The medium was a young lady by the name of Anna Rasmussen. The results were positive but not sensationally so. They did not come to public notice.

Not until 1945 when they were referred to in a feature article by the writer Jacob Paludan, who suggested that scientists look into the matter. A number of experiments were arranged at the psychological laboratory of Copenhagen University. The participants included a team of professional psychologists, Dr. Preben Plum, Franz From, M.Sc., the well-known spirit photographer Sven Türck, Jacob Paludan, and the chairman of the Society for Psychical Research, who was characterized in the daily Politiken like this: “…a man of pronounced features, with an ascetic and clerical appearance, quite sympathetic although his belief in spirits is just as ardent and fanatical as is the evangelist’s in the Holy Trinity.” And then, of course, there was the medium. By now her name was no longer Anna Rasmussen, but Anna Melloni. This should ring a bell with all who have heard of Danish spiritualism. Or start a siren, rather.

When the experiments were finished a statement from the three scientific supervisors was issued through Ritzaus Bureau. It said that distinct swings had been observed in the two pendulums suspended in a glass cabinet on a table in front of Mrs Melloni. Simultaneously it was registered by sensitive measuring instruments that the table was “subjected to mechanical actions precisely in time with the swings of the pendulums”. Moreover: “As soon as the cabinet with the pendulums was suspended in strings from the ceiling, so that it was a few centimeters above the table and not touching it, no pendulum swings occurred.” The signers

concluded: “Thus the result of the investigation is that the demonstrated phenomena can be wholly ascribed to mechanical causes.”

In plain language: Mrs Melloni had pushed the table!

And so the journalists were writing gleefully once again, and people were laughing at the gullible psychic researchers and their spirits and pendulums. But Anna Melloni was not put off by one solitary defeat; she enjoyed playing the part of popular medium and was not going to spirit herself away. She next took part in the seances held in the apartment of Sven Türck – the high-water mark of Danish spiritualism. On these occasions the spirits would tear off people’s trousers and shoes, heavy dining tables sailed in the air and chairs went flying over the heads of the participants. All of this is preserved in photographs and writing in the book by Türck, “Jeg var dus med ånderne” (I was a friend of the spirits), in which Mrs Melloni and her Egyptian spirit guide Lazarus are the central figures.

In the spring of 1950 this medium of nation-wide fame was to demonstrate her powers in the house of Dr. Preben Plum in Vedbæk. The seance was attended by a select circle of persons, among others Minister of Education Julius Bomholt, Karl Bjarnhof of the National Danish Broadcasting System, and writers Jacob Paludan and Aage Marcus. Mrs Melloni, however, did not know that “candid camera” was present as well. All that went on under the table was filmed, and the phenomena that seemed so impressive and spirited were soon revealed to depend on sleight-of-hand – sleight-of-foot, to be precise. The film was screened at the newsreels. A knockdown to Melloni and the spirits, and a bad name to all psychical research in Denmark.

To the society the years from 1950 to the early 70’s were meagre. The public interest in the paranormal veered from levitating tables to flying saucers. During this period the Danish UFO movement flourished, and the subject of extraterrestrial visitors was pursued with as much religious fervour as had earlier been bestowed on spiritualism. Meanwhile parapsychology was leading a shadow life. The only piece of extrovert activity the society could account for was a survey of the Danish population’s attitude towards paranormal experiences, made in co-operation with Gallup in 1957. This study showed that 11 percent of the adult population had had some kind of supernatural experience, and that the majority of mysterious experiences occurred in dreams. The typical “recipient” of supernatural phenomena was female, more than 35 years of age, and living in Copenhagen.

The society organized study circles for members, lectures were delivered, meetings held in the winter season, things were going by routine. The membership oscillated between 80 and 100. The economy didn’t leave much room for excesses such as psychical research. But thanks to a yearly grant from Parapsychology Foundation the society was able to build a well-stocked library.

In the late 1960’s public interest in the mysterious began to change. It all started with The Beatles going to India. And in the avalanche of new values set off by the flower-power generation the “spiritual side of things” came to be rated highly. Wisdom of the East, meditation, the Tibetan Book of the Dead, I Ching. Astrology was back with a vengeance, and interest in parapsychology was renewed. The secret life of plants, altered states of consciousness, and pyramid energy were hot topics. This was the dawn of the New Age.

At the general meeting of the society in 1974 it was decided to join forces with Strube Publishers. Psykisk Forum, the magazine published by Strube, would henceforth be the bulletin for the members of the society. And the other way round, all subscribers to Psykisk Forum would automatically be entered as members of the society. The inclusive price for membership and subscription was 50 kroner. To the Society for Psychical Research this was a highly successful move. In 1975 the membership jumped from 100 to 1000!

The increased income from subscriptions enabled the society to invite the big guns in parapsychology to lecture. In the second half of the 70’s most of those who had a say in parapsychology visited Copenhagen. Helmut Schmidt, W.G. Roll, Martin Johnson, Montague Ullman, Stanley Krippner, Milan Ryzl, and others. A star shower. These were good times. Parapsychology Foundation held an international conference in Copenhagen in 1976. And the committee of the society ventured to realize an old dream. In 1980 a fund was established to support Danish research in parapsychology.

Unfortunately, only a single project came into existence. A grant of 20.000 kroner was made to three persons who wanted to make a documentary of the trance dance of the Kalahari Bushmen. This drained the fund – and furthermore it gave rise to a bitter confrontation at the society’s general meeting in 1988. This confrontation, however, was really about something more fundamental: which line the society should take.

One wing was headed by chairman Kaare Claudewitz and vice-chairman Leif Mikkelsen. They had resigned prematurely out of anger with persons in the committee who, as they put it, “have been directing their efforts toward making the society more “occult” and “folksy”, and who think that our lectures should be popular first and foremost, not attaching too much importance to scientific standards.” As a contrast to this Claudewitz and Mikkelsen emphasized the preamble of the society which said that “parapsychological phenomena should be discussed and investigated in an unbiased and scientific spirit”. They wanted the society to operate in a more serious and critical manner, and the research fund to support laboratory experiments instead of anthropological expeditions such as the “Bushman project”.

This, then, was the scientific wing. The other wing was lead by committee members Klaus Aarsleff and Else Kammer Laursen who represented the occult and folksy side.

“Nothing good will come of trying to reduce man’s most enigmatic talents and powers to material phenomena,” Klaus Aarsleff wrote in the members’ bulletin. “Dragging the mysteries of the soul into the laboratory is equivalent to playing Mozart on a synthesizer. It’s just no-go.”

Else Kammer Laursen was of a similar opinion. Her contribution to the debate in advance of the general meeting is a paper central to the history of the society. It marks the official transition from objective science to subjective pursuit of the mysterious.

“Kaare and Leif subscribe to an old-fashioned academic point of view,” she wrote. “They sit around waiting for the final irrefutable proof of parapsychology to drop out of the sky, and for a big nice academic professor to come hurrying up, patting them fatherly on the shoulders, thanking them for their perseverance and proper set of mind … Others, including myself, don’t care much for that kind of thing. We have transcended our concerns about authorities and by and by lost our polite patience which will never pay off. If parapsychology isn’t acceptable in academic circles, then why shouldn’t we accept it for ourselves and start from there? Some of us frequently have parapsychological experiences. Do we need a professor to confirm it? We know it quite well ourselves.”

Parapsychology, she went on, “is also about having the courage to define and follow your own road, to create your own identity” – and especially “to be sympathetic to personal accounts of fantastic phenomena. That is where living parapsychology blooms, and that is the direction I think many of us want to take.”

And that is where they went. At the general meeting on May 19th 1988 Claudewitz and Mikkelsen were browbeaten; the society said goodbye to the scientific method and dozed off in a sweet-smelling New Age reverie. In the following years lectures given under the auspices of the society included such topics as the chakra system, pixies and trolls, crystal healing, numerology, iridology, and astrology. The members’ bulletin was brimming with personal accounts of fantastic phenomena. Occasionally, some members might touch

on ESP and psychokinesis, but the main course would always be astrology, reincarnation, orgone energy, and the like. Any subject was acceptable. In 1992 a woman disposed of nine and a half pages telling how she had communicated with space beings by means of a pendulum. This might have been the nadir of the society; but there was still some way to go.

When an extraordinary general meeting was summoned on November 27th 1994, the chairman did nothing to hide that things had been brought to a crisis. The society had been put under administration with legal aid.

“The cause of this unusual and unfortunate situation is mainly the library committee’s failure to submit accounts for several years,” he wrote. “In the course of 1994 the situation has become critical. Arbitrarily and in open contravention of the conditions of the charter, Birgit Tofte-Hansen has appointed herself administrator of the library fund. She has drained the library’s cheque account of an amount to the order of 10.000 kroner, for unknown purposes, and has removed the vouchers and our lists of members. Since the beginning of this year all efforts to bring her to reason have been in vain…”

The society managed to scrape through. But, as is often seen in near-death experiences, it was never the same afterwards.

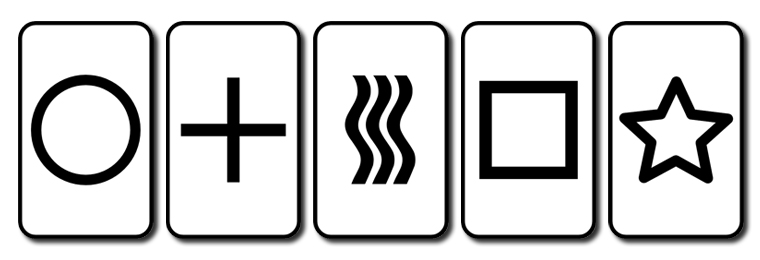

Nowadays the remains of the society carry on their activities unnoticed by the public. We ought to think kindly of the members as they struggle towards the society’s centenary. Those of a modern spirit should send out a feeling of universal, golden, divine love. If you are more old-fashioned, you may try one of the five symbols below.